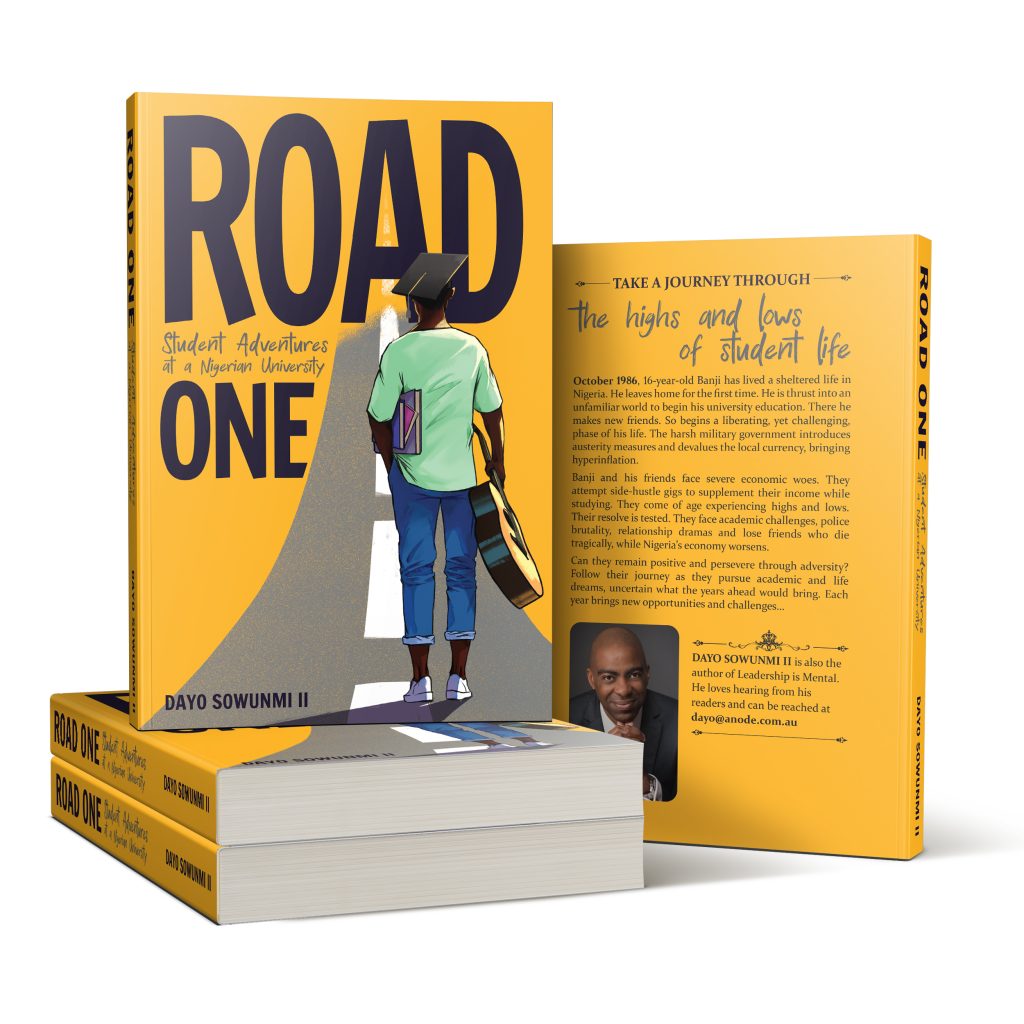

Excerpt from Road One

Grab your copy of Road One here.

Banji’s bunkmate Theo was a direct entry Year 2 Geology student. Year 2 students were called “senior Jambites”. First-year students like Banji were just called “Jambites”. Theo had previously attended a polytechnic college where he obtained his OND (Ordinary National Diploma) and HND (Higher National Diploma). These diplomas allowed Theo to be directly admitted into Year 2 of the four-year Geology course at the university. After working professionally for three years, attempting the JAMB examination every year, Theo was overjoyed to have finally made it into university. However, he was under no illusion that the road ahead would be easy. Right from that first weekend when fellow Jambites arrived on campus, Theo was diligently reading through textbooks, which he had purchased immediately after he received his offer of admission. At 27 years of age, Theo was about a decade older than most of his roommates, who promptly and respectfully started calling him Ẹgbọn Theo. Ẹgbọn is the Yoruba word used to refer to one’s elder sibling or kin, or to show deference towards a colleague, say five to ten years one’s senior. Theo stood a few inches below five feet tall, with a solid build. He had a no-nonsense air about him, paradoxically combined with an acute sense of humour.

Faloye Olubi was a first-year Economics student. Often dressed in native attire, the Adirẹ-wearing Faloye was exceptionally proud of his culture. For his first day on campus, he wore a bright adirẹ (tie-dye) outfit. The traditionally-cut loose-fitting top (buba) and matching trousers (ṣokoto) was appropriate dress for the cooler mornings and swelteringly hot afternoons typical of the current Harmattan season. While packing his suitcase for university, Faloye had selected the first outfit he would wear on the official start to his higher-education journey. The outfit he chose was his favourite, a multi-coloured adirẹ buba and ṣokoto outfit, starched enough to emphasise the edges without being excessively creased as other people were prone to wearing. Predominantly green in colour, the fabric pattern featured white, black, red and yellow splotches, like cosmic images of nebulae. He always wore leather wristbands, except for when having a shower. He bought the wristbands in Sabo, the name commonly given to the part of a city predominantly inhabited by Hausa people, who had relocated from northern Nigeria. It was similar to how, in Western cities, the name “Chinatown” is given to the part of the city largely occupied by people from Asia.

Faloye remembered the Malam from whom he bought the leather wristbands. Malam is the courteous way to address a man knowledgeable in Koranic matters. Slowly twirling a set of prayer rosary beads between the thumb and forefinger of his right hand, the Malam had picked out the wristbands with his idle left hand.

Shortly after meeting Banji, Faloye had already uttered several Yoruba proverbs from his extensive repertoire, and demonstrated his penchant for using ‘big’ English words while speaking. “There aren’t enough superlatives to describe the magnitude of the event,” he remarked, referring to the arrival on campus of first-year students. “If you are given a gift you don’t want, you reject it into your pocket,” he noted later, regurgitating something his parents had taught him. According to Faloye, one should keep such an unwanted gift because it may be needed later, or else give the gift to someone else who had a much higher need for it. When asked his opinion on the cases of candidates yet to gain university admission despite multiple attempts, he replied with another proverb. “Ki a to bẹ́’gi ninu igbo à á fi ọ̀ràn ro ara ẹni wò.” (“Before cutting down a tree in the forest one must first consider things from the perspective of the tree.” In other words, it is important to demonstrate empathy towards others). He added a second proverb to reinforce his opinion: “Ọwọ ọmọde kò tó pẹpẹ ti agba kò wọ keregbe.” (“Just as a child is too short to reach the high shelf so is an adult’s hand too big to enter a small jar.” In other words, everyone has something that they are good at.)

Banji was surprised to discover that Andy Oyekan who had been a year senior to him in high school was allocated to his room. Andy explained to Banji that he had completed his A-Levels, thereby allowing him admission via direct entry into second year to read Building Technology.

Another student in Banji’s room was simply referred to as ‘Green Book’. A philosophy student, the 24-year-old had completed his A-Levels at Oyo State College of Arts and Science (OSCAS), situated in Ife town. Like Ẹgbọn Theo and Andy, Green Book was admitted via direct entry, commencing his higher education in second year. He possessed a small green booklet that purported that the man spotted at the garden tomb was not the resurrected Christ, but merely a gardener tending the garden. Green Book was quick to share this viewpoint with anyone and everyone he met. His opinion on the matter was widely unpopular among the other roommates. His views brought controversy and friction with his roommates, which did not faze him as he fervently clung to his position.

Banji learned that some of his other roommates had a similar experience to him, with their parents travelling with them to the campus on the first day. Some students lightly teased him for being an ajẹ butter, someone who had lived a sheltered life. The literal translation from the Yoruba language is “someone who eats butter”, in contrast to people from harsher upbringings who rarely ate butter, but would instead consume less-expensive margarine, or even bread without butter or margarine. They had travelled by public transport and were proud of it.